learning to swim

"All water has a perfect memory and is forever trying to get back to where it was."

Dear friend,

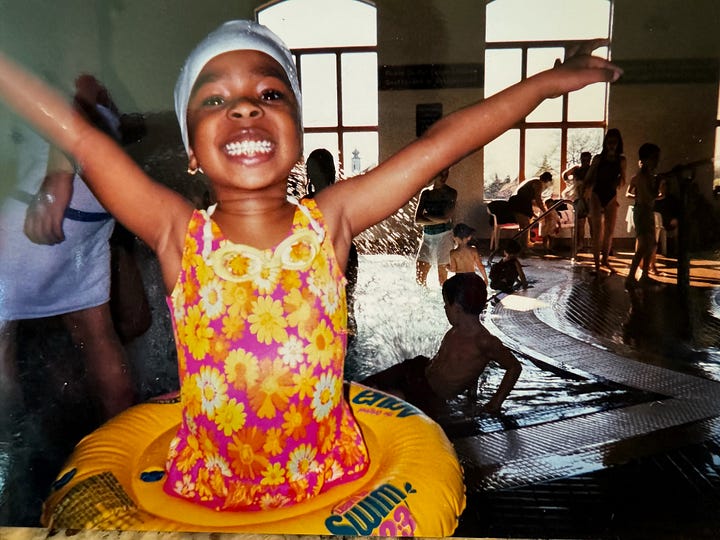

A few weeks ago, my mom came to visit me in Chicago and brought a small stack of nostalgic photos with her. One of the images was a snapshot of me at maybe six or seven crouched on the beach. I remember the short vacation my mom and I took that summer to a lodge near the coast of Lake Michigan and how enchanted I was by the endless water. Part of what drew me back to the midwest after a decade living in Texas is encapsulated in this photo—my wonder, delight and love for the one terrain that’s always felt the most like home: the Great Lakes region.

For much of my adult life I’ve been both mesmerized and terrified of water. As one of the only Black girls in my middle school and high school, I dreaded pool parties throughout my adolescence. The weight of my body—its Blackness—was something I carried around every day. At the pool or the beach, the weight of it drowned me before I even dipped a toe in the water. I would envy the white girls who dove in with abandon, not afraid of ruining a fresh relaxer or drowning. The tight swim caps and orange arm floaties of my childhood were no longer socially appropriate. I felt myself anchored on the sideline, ill-equipped and terrified of what the water might do to my body; how it might reveal to others my innate wrongness. My “defectiveness” felt metaphorically and literally laid bare.

As an adult, I’ve been fortunate to encounter some of the world’s most beautiful bodies of water. I’ve gazed at white sand beaches, marveled at frothing waves and turquoise cenotes, and watched waterfalls transform into mineral pools. In each instance, I kept me body safely at shore, occasionally letting my legs kick in the water while a gripped a nearby rock or requesting myself to wade at the shallow edges of the water and the shore. I volunteered to take photos of my friends as they bobbed around and kept watch over beach bags. I knew that even with a life vest or a floaty, my overwhelming anxiety would make the experience of being in deep water tortuous.

Last summer, I watched three of my closest friends slide into cool fresh water, naked at sunrise, and remained fully clothed on the overlooking cliff. Amidst the calm and beauty of the morning, I also felt acute sadness. My fear was calcifying, creating a wall between me and the life I wanted. A life that was arms length away but I dared not reach toward, for fear I’d lose my grip.

I’ve always known that the fear I carried wasn’t entirely my own. I grew up in a family of people who couldn’t swim. Swimming wasn’t something we, Black people, did. As a child, running around splash pads and wading in shallow pools were activities sprinkled throughout my summer breaks, but there were no models of what it looked like to love and be loved by water as an adult. This void made sense as I got older and understood that public pools in Detroit remained sites of segregation well into my mother’s childhood.

In a poetry class this Spring, I remember reading and re-reading Felicia Zamora’s poem “Bodies & Water,” and murmuring the last line to myself like a mantra: You cannot remove water from water, sea from sea. This was right around the peak of my obsession with Jamila Woods’ newest alum, Water Made Us. I experienced in her artistry the reverberations of the Toni Morrison quote that inspired the albums’s title: “All water has a perfect memory and is forever trying to get back to where it was.”

I tried to make peace with these words in my body. What does it mean to reclaim or return to my relationship with water? What does it mean to heal something generational through my body? How could I open up a portal for possibility by removing the growing mass of fear that blocked and burdened me? What would it take to cut the strong synapsis, built over lifetimes, between panic and water?

This May, after years of writing learn to swim on my list of New Years resolutions, I enrolled in swim classes. After calling city parks (classes were paused until the fall when full-time staff returned), trying to complete online enrollments (the ineffectiveness of public services websites never ceases to amaze me), and spending a long time at the reception desk of my local YMCA, I finally secured a spot in an adult beginners class.

The accomplishment I felt as the receptionist confirmed the class date and time was cut by a sharp, bitter dread. At home, I rummaged through my cabinets for a suitable bathing suit and scoured the internet for a swim cap. The night before my first class, I barely slept and arose before my alarm.

After navigating the maze to the locker room and then to the pool, I sat at its edge with my toes dipped in the chemical-blue water. Soon, other students arrived and so did the teacher—all of them Black women. I found myself smiling as we spoke about the struggle to find effective swim caps and how hard it was to trust the water. Our teacher asked about past traumatic experiences with swimming and let us acclimate to the pool slowly. I left that day feeling, for the first time in my life, that if I just kept showing up and trying, I could learn how to swim.

The three months that followed were hard. It was hard waking up early on a weekday to submerge my body in cold water. It was hard discovering time and time again that my various combination of swim caps had done effectively nothing to shield my hair from the chlorine. It was hard trying to quiet the part of my brain that would scream at me each time I engulfed my head under water or gravitated to the deepest edge of the pool.

One particularly challenging day last month, I attempted to swim the length of the pool and stood up halfway, panicked and out of breath. Exasperated, I told my teacher that I couldn’t move past the fear of drowning. She looked me in the eyes and opened up the palm of her hand. “Give me your fear,” she said. I looked back at her and did what she said, placing my invisible fear in her hand, and let myself be a little girl under the guidance of a capable adult.

That day I swam the full length of the pool.

Next month, I’ll move into an intermediate swim class. The fear that was so sharp and vibrant for years has softened and dulled. I’ve tried to make my way to the lake as often as possible this summer. I practice dunking my head fully underwater and try to recode the waves pushing against my body as playful, not threatening. I’m still happiest with a floaty and a life guard nearby, but I can feel my confidence growing. This confidence isn’t necessarily in my abilities as a swimmer but in the water’s ability to hold me up.

There’s a belief that used to live theoretically in my mind and now lives tangibly in my body: that I am water and earth. That the water knows me and I know it. That, if I lead with humility and love, the water will love me back. I feel it kissing my body, lapping against the back of my neck, and carrying me with ease. There’s a kind of innocent joy returning to our relationship that I thought was lost. It’s the joy of being free—free in my body and in these bodies of water that have always known me. A place I come from and am slowly returning to.

With love,

Jas

Jasmine, this piece is so beautiful. Thank you for sharing about your relationship to water. This morning, I meditated and fought between two different visualizations. When I allowed myself to surrender, I visualized myself floating in the Caribbean sea at a beach in my father's homeland. Thank you for sharing 💛